In Adventist Healthcare Inc. v. Mattingly, the Maryland Court of Special Appeals (COSA) was asked to consider whether a mother’s decision to cremate her son’s remains amounted to the destruction of evidence in a subsequent lawsuit for medical malpractice. The COSA ruled that having remains cremated does not constitute spoliation of evidence in a subsequent malpractice case. The Court held that family members have no duty to preserve evidence from the body or allow potential malpractice defendants to examine the body independently.

Facts of Adventist Healthcare Inc. v. Mattingly

The decedent (Mattingly) underwent surgery to reverse a colostomy at Adventist Hospital in Takoma Park, Maryland. Five days after the surgery, Mr. Mattingly died while still in the hospital. Mattingly’s mother was with him at the hospital when he died, and she immediately suspected that the doctors and staff had been negligent. She wanted an autopsy performed to learn the cause of her son’s death, but she didn’t trust anyone at the hospital to give her an honest opinion.

She ended up retaining a Maryland medical malpractice attorney who arranged for a private autopsy to be performed. Neither the hospital nor the surgeon (who would later be named as defendants in the malpractice case) were notified of the autopsy or allowed to participate. After the private autopsy was completed, Ms. Mattingly had her son’s body cremated.

Not long after the autopsy and cremation, Mattingly’s mother brought a wrongful death lawsuit against the surgeon and the hospital. The suit alleged that Mattingly died because the defendants negligently failed to diagnose a bowel leakage after his surgery which caused a fatal sepsis infection. This allegation and Mattingly’s cause of death were based on the findings made in the private autopsy which found cloudy, dark fluid in Mattingly’s peritoneal cavity.

The case eventually went to trial in Prince George’s County. Defense counsel repeatedly argued that Ms. Mattingly’s decision to have a private, independent autopsy and then cremate the body afterward constituted a spoilation of evidence. The trial court repeatedly rejected these arguments, and the jury awarded Ms. Mattingly $1,350,000 in damages (reduced to $740,000 based on the statutory cap on non-economic damages).

Analysis and Holdings of Adventist Healthcare Inc. v. Mattingly

On appeal, the defendants once again raised the issue of spoliation of evidence. The COSA was asked to decide whether Ms. Mattingly’s decision to have a private autopsy performed and then have her son’s remains cremated constituted spoliation of evidence in the malpractice case.

The Court began its analysis with a summary of the spoliation of evidence doctrine. The Court explained that spoilation is based on the simple principle that a party should not be allowed to support or defend claims based on physical evidence that has been destroyed to the detriment of the opposing party.

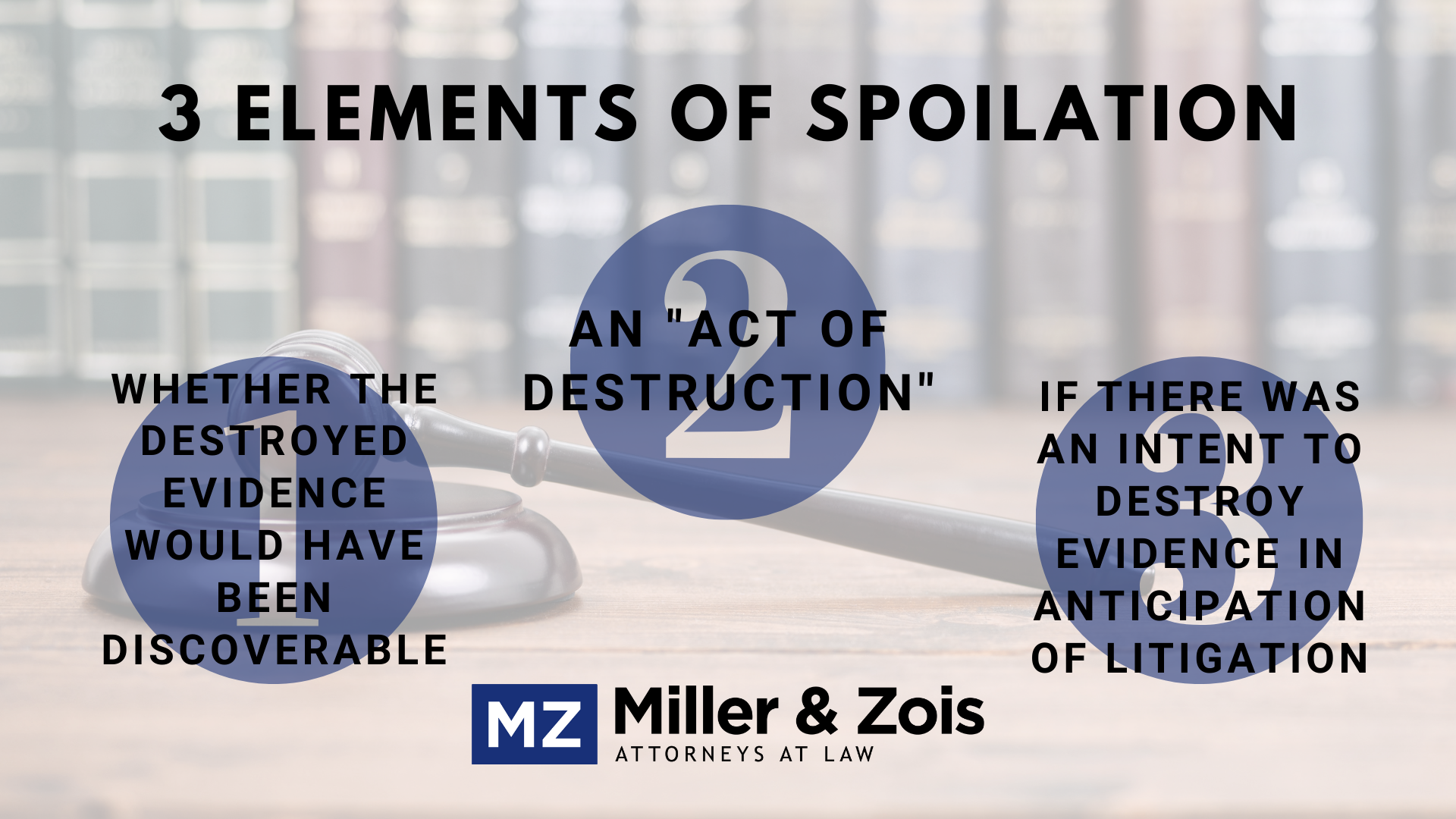

What Are the Three Elements of Spoliation?

This is just a reminder. When evaluating whether spoliation has occurred, Maryland courts look for three elements: (1) an “act of destruction”; (2) whether the destroyed evidence would have been discoverable; and (3) whether there was an intent to destroy evidence in anticipation of litigation (citing Cumberland Ins. Grp. v. Delmarva Power, 226 Md. App. 691, 705-06 (2016).

At issue in this case was whether there was an “act of destruction.” The defendants argued that the cremation of the body was an act of destruction of evidence, but Ms. Mattingly claimed that she was simply making final arrangements for her son’s remains. The defendants attempted to analogize this case to the circumstances in Cumberland Ins. Grp. v. Delmarva Power. In that case it was alleged that the house fire was caused by the power company’s defective utility box, but that box was disposed of just prior to filing suit. The court in that case held that the destruction of the utility box constituted spoliation because it was intentionally done right before the suit was filed and it crippled the defendant’s ability to disprove the allegations.

The defendants in the present case claimed that Ms. Mattingly’s failure to preserve her son’s remains was comparable to the failure to preserve the utility box in Cumberland. The Court was “entirely unpersuaded” by this comparison between a grieving mother cremating her son’s remains and the destruction of a utility box. The Court noted that decisions relating to the disposition of a deceased family member’s remains are inherently time-sensitive and emotional. The Court held that the cremation of a family member’s remains is NOT an “act of destruction” in the spoliation of evidence context. Moreover, the Court found no evidence to suggest that Ms. Mattingly’s decision to cremate her son’s body was an intentional effort to destroy evidence.

The Court based its holding on the fact that Maryland law recognizes that there is a major distinction between a human corpse and other types of physical evidence. In Maryland, surviving family members have the exclusive legal authority to make decisions about the property disposition of a decedent’s remains. See Md. Code Ann., Health Gen. § 5-509(c). The Court held that Ms. Mattingly was the person with legal authority as to the disposition of Mr. Mattingly’s remains under this statute. She did NOT have any duty to preserve her son’s remains to allow the defendants to perform their own independent analysis. No matter what evidentiary value the remains may have and no matter how much money might be at stake, a human corpse is not just another piece of evidence. Ms. Mattingly had every right to have her son cremated.

The COSA affirmed the trial court decision and found that it properly rejected the defendant’s motions for judgment and request for a jury instruction on spoliation of evidence.

Notes and Commentary on Adventist Healthcare Inc. v. Mattingly

I think the Court of Special Appeals made the right decision in this case, both from a legal and moral standpoint. The remains of a beloved family member cannot and should not be subject to the same rules as things like documents or other types of ordinary physical evidence. At some point, the law needs to give way to morality and human compassion. This is one of those situations. Just stop and think about the scenario that would result if this case were decided differently. Do we really want a rule that makes the preservation of a deceased family member’s corpse a mandatory pre-requirement to filing a medical malpractice case? Of course not. I applaud the Court for drawing the line in this case.

Maryland Injury Law Center

Maryland Injury Law Center