The Maryland Court of Special Appeals decision last week, in Choudhry v. Fowlkes 2019 WL 5677904 (Md. App., Nov. 1, 2019) is probably the most significant new development in Maryland personal injury law in 2019. Choudhry articulates a new 3-part rule for when plaintiffs in wrongful death cases can recover economic damages for loss of “household services.”

I love this case because it is a virtual treatise about how to put together a loss of household services case in Maryland. I don’t love the case because I think it raises the bar higher for making such a claim than most Maryland Circuit Court judges have been applying.

Loss of Household Services

Loss of household services is often a major component of damages in cases involving parents suing for the death of an adult child (or adult children suing for the death of a parent). This new rule will significantly affect the mechanics of pleading, proving, and recovering economic damages in these types of wrongful death cases.

Summary of Facts

Like all wrongful death claims, this case arose out of a family tragedy. In March 2013, a 22-year-old young woman died at Maryland General Hospital (UMMC Midtown) from complications related to a severe infection in her leg and groin. She filed a wrongful death action against the hospital and several of her daughter’s treating doctors. Besides pain and suffering for the death of her only daughter, the plaintiff sought economic damages for losing her “household services.”

Like all wrongful death claims, this case arose out of a family tragedy. In March 2013, a 22-year-old young woman died at Maryland General Hospital (UMMC Midtown) from complications related to a severe infection in her leg and groin. She filed a wrongful death action against the hospital and several of her daughter’s treating doctors. Besides pain and suffering for the death of her only daughter, the plaintiff sought economic damages for losing her “household services.”

The plaintiff was just 17 when she gave birth to her daughter. She raised her, admirable, as a single mother. At the time of her death, the daughter was still living with her mother. She testified that they planned to live together “forever” if possible. She also testified that her daughter performed many household duties such as cleaning and laundry. She could not drive so her daughter would always drive her everywhere like the store, the doctor, etc. To assist the jury in putting a value on these services, she testified that her daughter spent about 2 hours a day on these tasks.

After a week-long trial in Baltimore City, the jury found that one of the defendants was negligent and awarded $1,000,000 in damages. Half the damage award ($500,000) was for economic damages to compensate Fowlkes for the lost value of the decedent’s continued household services. Why did the jury value the loss of her daughter equally to the lost household services? I have no idea.

The doctor appealed the award of these economic damages based on 2 arguments: (1) the loss of general housekeeping services should not be recoverable as an economic loss; and (2) even if such household services are recoverable as an economic loss, Fowlkes did not present enough evidence to support these damages.

Legal Analysis of Damages in Wrongful Death Cases

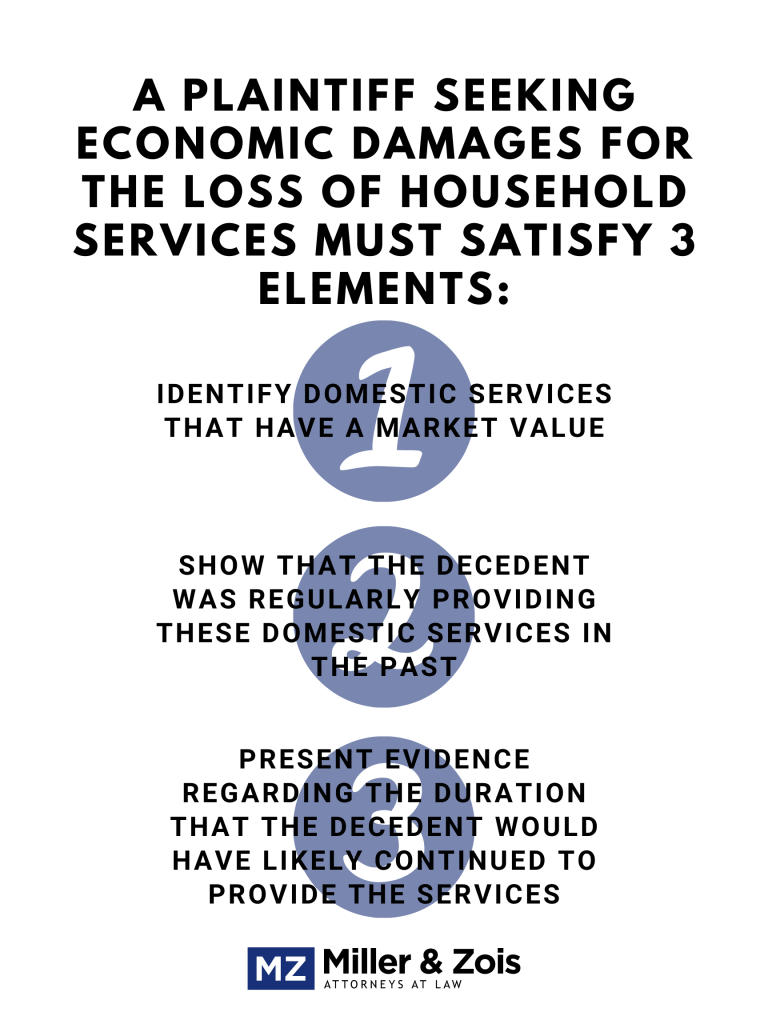

The opinion in Choudhry begins by acknowledging a lack of clarity in Maryland case law regarding the recovery of economic damages for loss of household services in certain death cases. To address this ambiguity, the Court stated that it was articulating a new 3-part rule to clarify when wrongful death plaintiffs can get economic damages for the loss of household services. Under this new rule, a plaintiff seeking economic damages for the loss household services must satisfy the following 3 elements:

- Identify domestic services that have a market value;

- Show that the decedent was regularly providing these domestic services in the past; and

- Present evidence regarding the duration that the decedent would have likely continued to provide the services.

The Court explained each of these 3 elements in further detail.

Identification of Domestic Services with Market Value

To satisfy this first part of the test, a plaintiff must clearly identify specific domestic services or household tasks that have an “identifiable market value.” This includes tasks that might be hired out to domestic workers such as cooking, cleaning, landscaping, or maintenance and repairs. In the Court’s view, this requirement is necessary because:

Without such an identification of specific domestic services that have a market value, economic damages awarded for a generalized claim of loss of “household services” could problematically duplicate damages awarded for the nonpecuniary aspect of household services and allow a beneficiary to circumvent the noneconomic damages cap set forth in CJ § 11-108(b).

The “noneconomic” aspect of “household services” includes things that cannot be performed by hired help and therefore have no market value. These would include services such as affection, companionship or sexual relations.

Reasonable Expectation to Receive Services

The second element requires plaintiffs to present evidence showing that he or she had a “reasonable expectation” that decedent would perform the domestic services identified in part (1). The Court explained that in a case where the decedent is a minor child or a spouse, this element is automatically satisfied because the plaintiff has a legal entitlement to the services. Parents are entitled to services from their minor children and spouses may support. See, e.g., Jones v. Balt. & O.R. Co., 173 Md. 238, 244 (1934).

This element becomes an issue, however, where the decedent is an adult child or a parent and there is no legal obligation. In these situations, the plaintiff can establish a reasonable expectation by presenting evidence that the decedent was “regularly and consistently” performing the domestic services in the past. Occasional or isolated acts of assistance will not be enough. The evidence must show a regular pattern of behavior.

Likely Duration of Services

To satisfy the 3rd part of the test, a plaintiff must present evidence establishing how long they could have reasonably expected the decedent to keep performing the domestic services. This requirement is based on the general principle that damages may not be “speculative, remote, or uncertain.” Choudhry (citing Sugarman v. Liles, 460 Md. 396, 439 (2018).

The Court explained that in certain cases, the duration of services can be presumed from the relationship between the plaintiff and the decedent. For instance, the duration of services between spouses is based on the couple’s joint life expectancy. See, e.g., Sun Cab Co. v. Walston, 15 Md. App. 113, 143 (1972). Similarly, when damages for loss of services are sought between a parent and a minor child, the duration is presumed to last until the child becomes an adult. See, e.g., Michaels v. Methvargo, 82 Md. App. 294, 204 (1990) (recognizing the right to damages for loss of child’s services until the child reaches age 18).

Satisfying this 3rd element becomes more difficult, however, when the decedent is an adult child, a parent, or some other relation. This is because there is no presumption that an adult child will continue to provide services for any set duration. Where there no presumption of duration, the plaintiff must present evidence to establish a non-speculative length of time during which the decedent’s services would have continued. This evidence can include statements of actions by the decedent about their intention to continue providing services and life expectancy.

As examples, the Court in Choudhry cited a pair of New York cases. In Lang v. Bouju, 667 N.Y.S.2d 440, 442 (N.Y. App. Div. 1997) this requirement was satisfied with evidence that the plaintiffs’ 22-year-old son lived and worked on the family farm, had no intention of leaving and planned to eventually take over the farm. In Lee v. NY Hosp. Queens, 987 N.Y.S.2d 436, 41 (N.Y. App. Div. 2014), this element was established when evidence showed that deceased father planned to be lifetime caretaker for an adult daughter with special needs.

Holding

After articulating its new 3-part rule for recovering economic damages for loss of household services, the Court applied the rule to the facts of the instant case. In doing so, the Court ultimately concluded that the plaintiff failed to satisfy part (1) and part (3) of the test.

Regarding part (1) of the test, the Court noted that the plaintiff identified specific domestic services that her deceased daughter provided (cleaning, washing dishes, driving her to run errands, etc.). While these were valid “domestic services,” the Court held that the plaintiff failed to present sufficient evidence to establish the “market value” of these services of the plaintiff based on a discovery violation. Without that report, the Court held that there was insufficient evidence to assign any market value and submit the issue to the jury.

Even if she had satisfied this first element, however, the Court held that she failed to establish the third element because she did not offer evidence as to the likely duration of the services. Specifically, she presented no evidence that her daughter, who was at the start of her adult life, planned to live with her mother and continue providing the services indefinitely. The reason she did not present this testimony is, well, how could she? Was she going to tell her daughter would live with her until she died? She was 22! The mother’s own testimony was that she wanted to live with her daughter forever, was not enough. This makes sense, right? I want my kids to live with me forever. But it will not happen.

Based on its holding that Fowlkes did not satisfy 2 out of the 3 required elements, the Court vacated the jury’s award of $500,000 in economic damages.

Notes and Comments

This is actually a very significant case from the Court of Special Appeals that could have a major impact on wrongful death cases in which the decedent is an adult child, parent, or anyone other than a child or spouse. Maryland’s cap on pain and suffering for wrongful death means that economic damages are often a big deal in these cases.

If you want to recover economic damages in these types of death cases, you need to have a working knowledge of the requirements set forth in Choudhry. It really is a great road map. Establishing each of the three required elements should not be difficult in most cases (although it was probably impossible in this case with a 22-year-old girl). It is easy to identify domestic services with a “market value.” Getting testimony about reasonable expectations and likely duration of those services should also be fairly easy in most circumstances.

I don’t think there was any way to get this case to a jury in a way that would have satisfied the court, even is the plaintiff had been given the virtual “how-to” guide that this case provides. Setting aside the expert report being excluded (part 1), how could she have given credible testimony that her daughter planned to live with her forever? (Maybe perhaps she would have continued to provide the same services even after she left?) I also think it would have helped if it was more specific household services than driving and other general household services.

The decision in Choudhry arguably raises the bar for recovering economic loss of services damages in these cases. However, the decision is helpful to personal injury and medical malpractice lawyers because it provides plaintiffs with very clear guidelines on how to satisfy this new test.

Maryland Injury Law Center

Maryland Injury Law Center