Anyone who can blithely throw together a joint tortfeasor release in a malpractice or another complicated tort claim without reading the case law 10 times is an absolute expert on these releases or suffers from an extreme case of irrational confidence. Usually, in my experience, it is the latter.

The job of the Maryland appellate courts in dealing with this unavoidably complicated maze is to give Maryland attorneys clear and concise rules in navigating the path. Given a chance to do this in Mercy Medical Center v. Julian, the court took what I think – and more important the dissent thought – is a different path that might lead to more confusion or, maybe better put, lack of trust that the settling parties know the ramification of the settlement. If I’m right about this, it will have a chilling effect on parties settling in a case with multiple defendants.

The job of the Maryland appellate courts in dealing with this unavoidably complicated maze is to give Maryland attorneys clear and concise rules in navigating the path. Given a chance to do this in Mercy Medical Center v. Julian, the court took what I think – and more important the dissent thought – is a different path that might lead to more confusion or, maybe better put, lack of trust that the settling parties know the ramification of the settlement. If I’m right about this, it will have a chilling effect on parties settling in a case with multiple defendants.

This case involved a lawsuit alleging that medical malpractice caused cerebral palsy and the ultimate death of a child. Just awful. (I wanted to throw up a picture with this post but I could not think of one even remotely appropriate.) Plaintiffs and Mercy Hospital settled out before trial. The release – called in Maryland a “Swigert Release” – with Mercy provided for a pro-rata reduction of any judgment against doctor defendant if Mercy was found to be a joint tortfeasor.

Before trial, the doctor’s attorney sought and received the production of the release with Mercy. The doctor did not cross-claim, third-party, or otherwise, make any effort to have a determination made whether Mercy was liable. The jury hit the doctor with an $8,000,000 verdict, reduced to just under $2.2 million by the cap on non-economic damages.

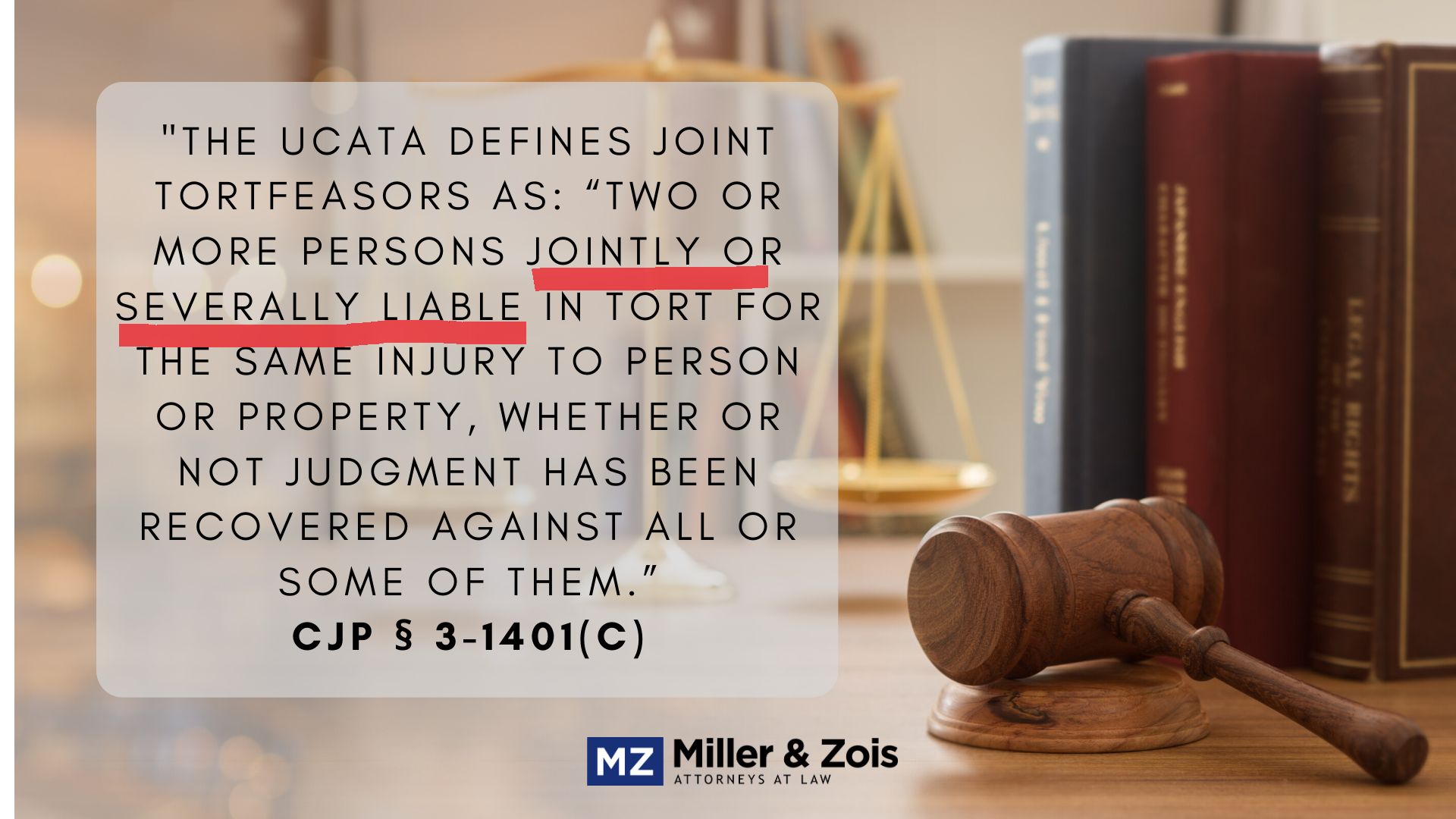

So who pays what? Shockingly, a disagreement ensued so everyone sued everyone again. The doctor sued Mercy for contribution. The plaintiffs – who just want their money – sue the doctor again, asking the court to rule that he is not entitled to contribution. The doctor, seeking a declaration that he was not entitled to contribution. The Maryland Court of Special Appeals lessened this train wreck a little by appropriately merging the two actions. The issue before the CSA was whether the doctor may pursue contribution against Mercy after it had settled with the plaintiffs when it did nothing to push the first jury to make the call whether Mercy is on the hook. The parties to the release – strange bedfellows of the plaintiffs and Mercy – argued that the doctor did not preserve his contribution rights as required by the Maryland Uniform Contribution Among Joint Tort-Feasors Act. So their release extinguished any right that the doctor had to seek contribution against Mercy because he did not join Mercy as a third-party defendant in the original action after it was dismissed as a party. The Court of Special Appeals found that there was “no Maryland statute, case law or rule that prohibited an independent contribution action under the circumstances of this case.”

The Maryland “supreme court”, the Maryland Court of Appeals, somewhat vaguely agreed to this “Yeah, okay, under these facts” ruling.

The Maryland “supreme court”, the Maryland Court of Appeals, somewhat vaguely agreed to this “Yeah, okay, under these facts” ruling.

The “dissent” – authored by Judge Robert N. McDonald and joined by Judges Glenn T. Harrell Jr, and Chief Judge Robert M. Bell – agreed with the majority opinion but wanted the court to make a real rule to avoid confusion and uncertainty for Maryland lawyers who want to settle again one defendant. Maryland law encourages settlement and does not want squeamish defense lawyers and adjusters – who fear making a mistake that gets them in trouble more than they do a verdict – feeling that they can’t trust the settlements they are making.

No doubt the parties to medical malpractice and other tort litigation will accommodate their practices to whatever rule we ultimately adopt for the effect of particular types of releases under UCATA. It is important, nonetheless, that we make whatever rule we adopt clear so that they may make the accommodation.

It is sometimes not so important what rule is adopted as that some rule is clearly adopted.

I could not agree more. For added fun, McDonald uses some Judge Harrell-like phraseology to describe the problem:

For example, there is no moral imperative that directs the choice between requiring drivers to stay to the right side of the road or to stay to the left. But the choice must be clearly made.

If not, even the best engineered road will experience head-on collisions.

What is the way out of this mess? Well, the doctor could have just filed a third-party claim. But malpractice defense lawyers hate this — they love the “all for one, one for all” strategy, even in a case where it drives their client off the cliff. Similarly, Mercy could have gotten an adjudication on the merits by moving for a summary judgment requiring the doctor to put up or shut-up in its claims. But for tactical or political reasons, that path was not explored in this case.

I could make this post three times as long. But I think this is enough for one day of joint tortfeasor releases. You can read the full opinion here.

Maryland Injury Law Center

Maryland Injury Law Center