U.S. District of Judge Richard D. Bennett issued an opinion Monday in Robertson v. Iuliano, an informed consent medical malpractice lawsuit against a neurosurgeon and St. Agnes Hospital.

The first question you might have is how this malpractice case ended up in federal court instead of Baltimore City Circuit Court, where the claim was filed? Good question, my dear reader. Only a crazy plaintiffs’ med mal lawyer would file in federal court over Baltimore City because Baltimore is just a much better venue.

So what gives? Apparently, after committing an alleged tort in Baltimore City, the doctor moved to Virginia. It seems odd – in fact, crazy – to me that a defendant who commits a tort in Maryland could avail themselves of removal by moving away after the fact. But, in an earlier opinion, the court opined that the plain meaning of the removal statute mandated federal jurisdiction. It is a silly law, but it is the law.

Facts of Robertson v. Iuliano

Anyway, I know little about the underlying facts. But the case sounds weak to me. The plaintiff claims he would not have undergone back surgery to repair a disc at L4-L5. He suffered from moving a dryer for a customer while working at Lowe’s Home Improvement had he known that he might get an infection from the surgery.

St. Agnes and Neurosurgery Services, LLC and St. Agnes Healthcare, Inc. were also sued. Still, the court ruled in their favor and found that they could not be held liable for Dr. Iuliano’s actions because they were not responsible for ensuring their doctors adequately informed their patients of the risk and because there was no actual or apparent agency. The court dismissed the informed consent argument because Maryland law is clear that the duty to obtain informed consent is the doctor’s job. There is no duty to the patient from the hospital unless they “specifically assumed the duty.” I’m not sure why this would be the law. But it is.

Efforts to Amend Complaint Failed

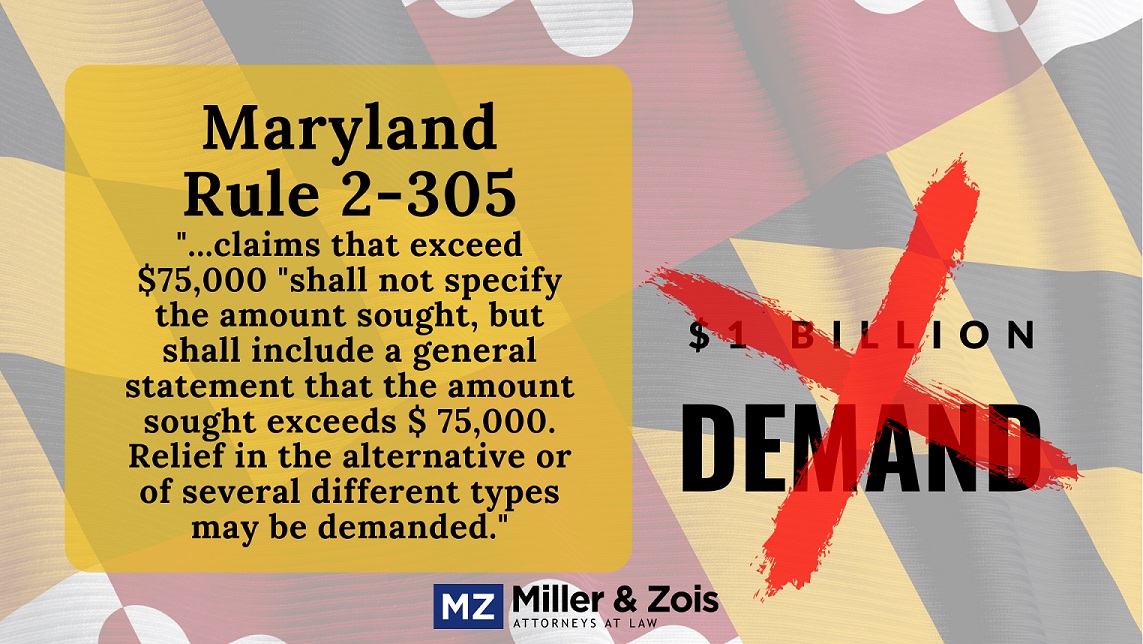

Before the trial, Robertson filed a motion to amend his complaint to clarify that the lack of informed consent included the failure to disclose alternative forms of treatment. He also wanted to increase the amount stated in his complaint. However, the court has denied his motion to amend the complaint.

Why? According to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, an amendment to a pleading should only be denied if it would cause prejudice to the opposing party, there was bad faith on the part of the person making the amendment, or if the amendment would be considered futile. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit has interpreted this rule to mean that amendments should be freely allowed as long as justice requires it.

The court agrees with this but says there are limits. The judge underscored that the deadline to amend the pleadings had already passed and that to be approved, the amendment must satisfy both the “good cause” standard and the standard set by Rule 15(a)(2) of the Rules of Civil Procedure. The court found that Robertson did not satisfy the “good cause” standard and determined that the amendment would be prejudicial to the doctor. The court concluded that allowing the amendment on the eve of a trial would be unfair to the doctor because discovery has been conducted concerning informing the plaintiff of alternative treatment methods. The amendment would essentially add a new claim to the complaint. So that makes sense.